HUNTINGTON — A group of conservative Republican residents in Cabell County, frustrated by what they described as long-standing political bias and retaliation from local leadership, attempted to run for local office in 2022. What followed was a three-year saga involving accusations of criminal wrongdoing, missed deadlines, and allegations of abuse of power by state election officials.

At the center of the controversy are Jan Hite King and Kimberly Maynard, both of whom were removed from the 2022 election ballot and later indicted by a grand jury in 2025—on misdemeanor charges that had already passed the statute of limitations.

Redistricting Sparks Confusion

In October 2021, the Cabell County Commission approved new voting maps after a statewide redistricting process reduced the number of magisterial districts in the county from five to three. Cabell County has long leaned Democratic, but in December 2021, a group of conservative, pro-Trump Republicans announced their intention to run for local office. They said their goal was to challenge what they referred to as the “Cabell County Mafia” and combat what they viewed as retaliatory actions against right-leaning residents.

In January 2022, Kimberly Maynard requested a copy of the updated district maps from the Cabell County Clerk’s Office. She was told by staff that the redistricting process was not complete and that no maps were available. At the time, Phyllis Smith, a Democrat, was the Cabell County Clerk.

Weeks later, County Commissioner John Mandt received the same response when he inquired about the new district maps.

When the candidate filing period began, a friend of Jan Hite King attempted to obtain the maps again but was told, “It’s not finished yet.” When asked how people could properly file to run for office without knowing their district, a clerk staff member reportedly shrugged in response.

Despite the filing period being underway, the Cabell County Clerk’s Office still had not distributed updated maps.

Filing Mishap and Misinformation

On February 2, 2022, Jan Hite King was still unsure which district she resided in. She consulted the West Virginia Secretary of State’s website, which listed her address in District 1.

When King went to file at the Cabell County Clerk’s Office on February 3, 2022, she was told by a clerk staffer that “We have to go by what the Secretary of State’s website says. It says that you are in district 2.” Confused, but trusting the clerk’s guidance, King changed her district from 1 to 2 on the filing form, paid the filing fee, and submitted her paperwork.

Two days later, King received a letter from Cabell County Attorney Ancil G. Ramey stating she had filed incorrectly and needed to refile in District 1—the district originally listed on the Secretary of State’s website and the one she had initially selected. King complied and refiled in District 1.

On February 11, 2022, King received an email from Ramey stating that if she did not rescind her filing, he would refer the matter for criminal prosecution. Donald “Deak” Kersey, Chief Deputy Secretary and Chief of Staff for the West Virginia Secretary of State, was copied on the email. King, now represented by legal counsel, was advised not to rescind the filing. Her lawyer argued that she had followed the district information listed on the Secretary of State’s website and the instructions in Ramey’s earlier letter.

Removal From the Ballot

Despite following the procedure and drawing first position on the ballot, King and Maynard were both removed from the ballot. No judicial ruling authorized the removal, and neither candidate was notified. King learned of her removal through a reporter from the Herald-Dispatch.

Neither King nor Maynard received a refund for their filing fees.

Soon after, King’s attorney received a letter from Kim Mason, an investigator with the West Virginia Secretary of State’s Election Division, stating that a complaint had been filed against King. Mason also contacted Maynard.

When King’s attorney requested a copy of the complaint, Mason refused, citing state code restrictions on disclosing complaint details. With no clear guidance, the attorney did not respond further to Mason.

State Investigator Meets With Candidates

King’s attorney received an email from Robert Hansen, an investigator for the West Virginia Attorney General’s Office. He requested a meeting to discuss the case. King, Maynard, and their attorney met with Hansen, bringing binders of evidence. Hansen did not request copies of the documentation. The meetings lasted 30 to 45 minutes and marked the final contact King had with him.

King’s attorney followed up, and Hansen stated that the case had been referred to the Cabell County Prosecutor. That office, citing a conflict of interest, forwarded the case to the Wayne County Prosecutor.

When King’s attorney contacted Wayne County, officials there had no information about the referral. Approaching the statute of limitations deadline in February 2023, King’s attorney followed up again. The office indicated that the matter was not a priority.

Misdemeanor Charges Filed After Expiration

All allegations from the Secretary of State’s Office amounted to misdemeanors:

- False Swearing: King and Maynard were charged under §3-9-3(a) for allegedly filing with incorrect district information.

- Aiding and Abetting: Because they notarized each others forms, they were also charged with aiding and abetting false swearing.

- Conspiracy: Prosecutors alleged the pair conspired under §61-10-31, a misdemeanor conspiracy statute.

Despite the misdemeanor charges, neither King nor Maynard had been subpoenaed. Investigator Kim Mason never contacted King directly.

After the statute of limitations expired, the case was transferred to Mason County Prosecutor Seth Gaskins. On April 4, 2025—more than two years after the events—King and Maynard were indicted by a grand jury. Legal experts noted that misdemeanor charges are rarely handled by a grand jury and are typically addressed in magistrate court.

King-and-Maynard-Indictment-1Before becoming the Mason County Prosecutor, Gaskins formerly worked as the an attorney for the West Virginia House of Delegates. In 2016, The Charleston Gazette-Mail reported that he controversially solicited campaign contributions for his wife’s House of Delegates campaign while he was on the job at the state capitol.

Secretary of State Goes Public

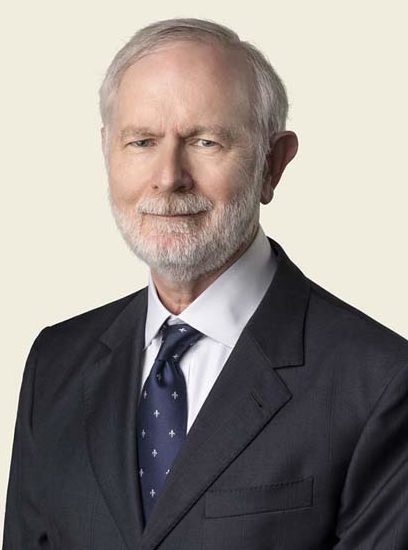

On April 7, 2025, West Virginia Secretary of State Kris Warner issued a press release announcing the indictments.

“Candidates are expected to provide accurate information on their Certificate of Announcement to ensure they are eligible to run for the office they are seeking,” Warner said. “Our Office will investigate and, where appropriate, refer for prosecution any allegation that a candidate provides false information on the certificate.”

Warner continued, “I want to recognize the due diligence and dedication of Kim Mason and Robert Hanson in thoroughly investigating these allegations. I also want to thank Prosecutor Seth Gaskins for presenting the evidence to the grand jury.”

The next day, Warner appeared on Eastern Panhandle Talk, where he accused Governor Patrick Morrisey of “inhibiting transparency” and abusing his authority after vetoing Senate Bill 369, which was a rules package that would have expanded the powers of the Secretary of State’s Office.

As the interview continued, Warner was asked about the specific details regarding the press release from the day prior.

Warner stated, that King and Maynard attempted to run in a county where they did not reside. In reality, both lived in Cabell County and filed to run for office within their own county.

“They basically lied and said that they served in the magisterial district of the county that they did not live in, and they conspired to do that,” Warner said on air. “This will go to trial now for two candidates that are accused of conspiring and lying on a Certificate of Announcement.”

Warner acknowledged that the charges were outside the statute of limitations but defended the prolonged investigation.

“These things take time. I know we’ve been asked, why… ‘This is 2022 and it’s now 2025.’ And we have to follow every one of these out to the end. We turn in information over to the prosecutor, and its up to them to decide whether they’re going to prosecute.”

Warner continued expressing “frustration” that they have encountered multiple occasions where local prosecutors refuse to prosecute their cases. This has led to their recent method of seeking a “special prosecutor” to act when local prosecutors refuse. He again, doubled-down, stating that his office will investigate and prosecute cases beyond their statute of limitations, even if it takes three years.

“The frustrating thing is we actually have… and I’ve got to be careful about what I say … and I have to be very general,” Warner said catching himself.

“… but we’ve turned situations over what we maybe believe is illegal voting to prosecutors and they don’t think it’s important enough with everything else they are doing to move forward. So, we will see if we can try to take it up in another county, or a special prosecutor, because we all know how important our elections are and every one of our votes are. And our office will follow these to the end, even if the investigation takes three years to present the information to the prosecutor, as was the case here.”

Charges Dismissed

On April 25, 2025, Jan Hite King and Kimberly Maynard appeared in court before Judge James H. Young Jr., who had been assigned the case following its transfer from Cabell County to Wayne County.

According to court documents, defense attorney Tyler Haslam opened by questioning why the case was being pursued more than three years after the alleged offense — well beyond the statute of limitations.

“West Virginia law is clear that misdemeanor criminal charges have to be commenced within one year of the alleged offense,” Haslam wrote in the defense’s motion to dismiss.

“The salient question is this: Why after more than three years since the alleged act occurred and more than two years after charges could have been brought under West Virginia law, has the Mason County Prosecuting Attorney decided to pursue charges now given that no criminal charges were filed by the Wayne County Prosecuting Attorney while he was in charge of the case?”

Citing State v. Leonard (2000) and State v. Bfasley (1883), Haslam argued that West Virginia law prohibits prosecution after the statute of limitations has expired.

“Not only should the issue of the statute of limitation be glaring obvious to the prosecuting attorney in this matter,” Haslam continued, “but even the Secretary of State’s own election manual outlines the one-year statute of limitation for misdemeanor offences and cites to the relevant statutory section for the one-year statute — ‘Misdemeanor offenses must be charged within (1) year of the offense.’ That makes the decision of Secretary of State Kris Warner to publicly crow about this case by issuing a press release and stating, in part, ‘This indictment, hopefully, sends the message that this alleged conduct will not be tolerated,’ all the more baffling. As Secretary of State Warner’s own election manual sets forth, the indictment is, at best, stale.”

“If there was an offense upon which a conviction could have been obtained,” Haslam added, “then criminal charges should have been filed no later than February 3, 2023; not presented to a grand jury more than two years late on April 4, 2025.”

In a short answer, special prosecutor Seth Gaskins attempted to justify the delay by citing West Virginia Code §3-9-24 (1978), which allows for prosecutions up to five years. However, that statute does not distinguish between misdemeanor and felony offenses.

In response, Haslam pointed out that a more specific statute passed in 2002 — West Virginia Code §61-11-9 — states, “A prosecution for a misdemeanor shall be commenced within one year after the offense was committed.” That statute supersedes the earlier and more general provision.

This interpretation, Haslam noted, had already been acknowledged by the West Virginia Secretary of State in the office’s own authorized election manual, which explicitly outlined that Chapter 3 misdemeanor offenses must be charged within one year under §61-11-9, whereas felony offenses follow the five-year limitation under §3-9-24.

“Why the Secretary of State’s Investigations Unit, the Special Prosecutor, is advancing the current argument is, at best baffling and, at worst, extremely troubling,” Haslam wrote.

Manual-for-Election-Officials-Excerpt

He also cited Stepp v. Cottrell (2022) to reinforce his point that specific statutes take precedence over general ones.

“The Supreme Court of Appeals has repeatedly held that specific statutes are given precedence over general statutes relating to the same subject matter and that specific statutory language takes precedence over more general statutory provisions,” Haslam stated.

“Twenty-five years ago, the Supreme Court of Appeals established that §61-11-9 is a specific statute of limitations for all misdemeanors, State v. Leonard (2000),” Haslam added. “W. Va. Code §3-9-24 does not make a distinction between alleged felony and misdemeanor crimes under Chapter 3. As such, W. Va. Code §61-11-9 is the specific statute of limitations that must be applied in this matter. Accordingly, the indictment should be dismissed.”

After reviewing the arguments, Judge Young agreed with the defense and dismissed all charges.

2025_05_01-Order-Dismissal-Prejudice

Warner Responds After Case Dismissed

Days after a judge dismissed all charges against Jan Hite King and Kimberly Maynard, West Virginia Secretary of State Kris Warner continued to publicly misrepresent the facts of the case and the law surrounding it during an April 30, 2025, interview on Eastern Panhandle Talk.

In the interview, Warner again falsely claimed that King and Maynard “lied” on their candidate filing forms, despite the information they submitted on their candidate forms had been directly pulled from the Secretary of State’s own website. Warner continued to characterize the pair’s actions as deliberate misconduct, even though a circuit court judge found that the charges were brought outside the legal timeframe.

“We just had a case down in Cabell County where two women lied about their location of where they were filing their candidate form and we presented the information, had to go to three different prosecutors to get them to carry this forward,” Warner said. “It went to the grand jury. We came back. They were going to be defendants and for whatever reason, the judge threw it out, said the statute of limitations has expired. We didn’t understand it that way.”

Then, Warner inaccurately claimed the statute of limitations for misdemeanor offenses in West Virginia is two years. However, under West Virginia Code §61-11-9, the legal limit for prosecuting misdemeanors is one year, as they were just notified by Judge Young.

Warner further stated, “We think, the way our attorneys read the law, that it was five years not two years.”

Legal experts have since confirmed that §61-11-9 is the controlling statute and has been recognized as such in multiple State Supreme Court rulings, including State v. Leonard (2000).

Despite the dismissal of charges, Warner doubled down on his office’s actions, saying, “There are so many cases that our investigative unit investigates. Quite frankly, we turn over quite a bit of information to prosecutors and they choose not to prosecute… We’re going to continue to stay on top of it.”

As in a previous interview, Warner again attacked Gov. Morrisey, accusing him of blocking “transparency” by vetoing Senate Bill 369 — a proposed rules package that would have granted Warner’s office sweeping new powers over investigations and censorship of campaign materials. Warner argued the bill was designed to expose “dark money” in politics, despite mounting evidence that his own campaign benefited from undisclosed political spending.

The irony was not lost on critics. Warner’s 2024 campaign for Secretary of State came under scrutiny after reports surfaced that recipients of loans from the West Virginia Economic Development Authority (WVEDA) — where Warner had served as executive director — funneled large sums into a federal 527 Super PAC, Conservative Policy Action. The PAC, in turn, received major backing from Conservative Policy Solutions, a 501(c)(4) nonprofit that does not disclose its donors.

Thomas Datwyler, who served as the principal officer for the nonprofit, was accused of wire fraud last year by the Conservative Nevada Leadership PAC (CNLP), filing a complaint with the Justice Department on July 26, 2024. As reported by The Hill, Datwyler also infamously served as the “shadow treasurer” for disgraced Fmr. Rep. George Santos (R-NY), who was sentenced to over 7 years on federal wire fraud and aggravated identity theft charges. Datwyler’s non-profit donated $96,500 to Conservative Policy Action, and was the largest sole contribution to an entity supporting Warner as a candidate for Secretary of State.

The scandal led to the resignation of Mark Scott, former cabinet secretary for the West Virginia Department of Administration and chairman of Conservative Policy Action. Scott was accused of soliciting campaign donations while on state duty.

On July 25, 2024, Warner’s Republican primary opponent, Ken Reed, filed an official complaint calling for a state investigation into what he described as “potential unethical dealings with state contracts” and “collusion” between Warner and Scott.

“As reported, this PAC focused on Kris Warner’s candidacy for Secretary of State,” Reed wrote. “I suspect there was collusion between Mr. Scott and Mr. Warner throughout the campaign, along with potential unethical dealings with state contracts.”

Reed’s complaint also referenced a possible ongoing investigation by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) into the PAC’s financial activities, though no public findings have yet been released.

Despite the controversy and judicial rebuke, Warner’s latest comments suggest he intends to continue leveraging his office’s investigative powers, even in legally and ethically questionable ways.

Was the Secretary of State More Interested in a Publicity Stunt Than Justice?

Legal experts say Secretary of State Kris Warner appeared to sensationalize the case by pursuing charges against Jan Hite King and Kimberly Maynard long after the statute of limitations had expired. They argue that the charges—centered on false swearing and conspiracy—were not only procedurally invalid but also stemmed from incorrect district information originally provided by Warner’s own office. Instead of acknowledging the administrative confusion, Warner escalated the matter into a public spectacle, culminating in a press campaign and media appearances that experts believe served more to bolster his personal reputation than to ensure electoral integrity. As a result, King and Maynard’s reputations were damaged by what some legal observers characterize as politically motivated overreach.

Administrative Negligence by the County Clerk’s Office and the West Virginia Secretary of State

The administrative failures in this case begin with the Cabell County Clerk’s office and extend to the West Virginia Secretary of State’s office. The Clerk’s office, led by Phyllis Smith, failed to provide accurate or timely information about the redistricting process, leaving candidates in the dark about which magisterial district they were eligible to run in. This confusion persisted for weeks, with the office repeatedly stating that the new district maps were “not finished yet,” even as the filing period for local candidates began. Such delays are particularly concerning given that the Clerk’s office is responsible for ensuring a smooth, transparent election process. Furthermore, the West Virginia Secretary of State’s office compounded the issue by providing inaccurate district data, which led to Jan Hite King and Kimberly Maynard mistakenly filing in the wrong districts. Despite these errors being traced back to their own offices, both the Cabell County Clerk and Secretary of State’s office failed to acknowledge their role in the confusion, which set the stage for the subsequent legal and political turmoil.

The Unusual Appointment of a Special Prosecutor

It is highly uncommon for a special prosecutor to be appointed after a local prosecutor has declined to pursue charges. The decision to bring in a special prosecutor in this case raises serious questions. When the Cabell County Prosecutor’s office chose not to pursue charges, citing a potential conflict of interest, the case was referred to the Wayne County Prosecutor’s office. However, when they also failed to act, the decision was made to appoint a special prosecutor. Legal experts are left to wonder why this decision was made, especially in a case where the statute of limitations had already expired, and no substantive new evidence had emerged. The appointment of a special prosecutor is generally reserved for cases where there is a clear and compelling need for independent investigation, but here, the situation appears to be driven more by political motivations than by any genuine legal necessity.

The Impact on King and Maynard’s Political Careers

The consequences for Jan Hite King and Kimberly Maynard have been far-reaching, particularly in terms of their political careers. In West Virginia, the Secretary of State’s office wields significant power, and accusations of electoral misconduct can be devastating. Both King and Maynard had their candidacies disrupted by legal challenges, with their names being removed from the ballot without due process. The public nature of these accusations and the media frenzy surrounding the case have damaged their reputations, making it difficult for them to recover politically. The Secretary of State’s decision to escalate the issue and pursue charges despite the expiration of the statute of limitations could be seen as an effort to neutralize political opponents, especially in a state with historically entrenched Democratic power. The allegations have left a stain on their political records, and it may be difficult for either of them to rebuild trust with voters in future campaigns. This case demonstrates the power the Secretary of State holds in shaping the political landscape, and raises ethical concerns about whether such power is being used to target specific individuals for political reasons.

The Statute of Limitations: A Legal Quandary

The legal principle behind the statute of limitations is that a person cannot be prosecuted for an alleged crime after a certain period has passed. In this case, the statute of limitations for the misdemeanor charges against King and Maynard had expired, and the case should have been closed. Pursuing charges after this period is seen as highly controversial, as it undermines the legal protections provided by this principle, which exists to ensure fairness and justice. Experts argue that continuing to investigate and prosecute cases beyond the statute of limitations not only violates these protections but also creates a chilling effect on political candidates, who may fear future retaliation over long-past accusations. In this instance, the Secretary of State’s office disregarded the expiration of the statute, leading to a situation where charges were pursued for purely political reasons, casting doubt on the integrity of the office.

The Ethics of Political Investigations and Legal Prosecution

The ethics of using legal mechanisms to pursue politically charged cases are central to understanding the motivations behind this investigation. Legal experts contend that the West Virginia Secretary of State’s office engaged in ethically questionable practices by pursuing charges against King and Maynard, especially when the underlying information was inaccurate and the statute of limitations had expired. The use of public resources to investigate and prosecute individuals over what could be seen as minor administrative errors — particularly when these individuals were political candidates challenging the status quo — raises significant concerns about the ethical use of power. Moreover, the decision to publicize the case widely, in what seemed like an effort to raise the profile of the Secretary of State’s office, calls into question whether the pursuit of justice was the primary concern or if it was instead a politically motivated maneuver aimed at discrediting political opponents.

Warner’s Push for Expanded Powers and Ethical Concerns

Kris Warner’s recent pursuit of expanded powers for the Secretary of State’s office is another troubling aspect of this case. This year, Warner pushed for a legislative package that would significantly broaden his office’s authority to investigate and prosecute election law violations, including forcing the Attorney General to pursue cases that Warner’s office deems necessary, without the Attorney General’s ability to decline involvement. Critics see this as an attempt to centralize power in the Secretary of State’s office, removing oversight and creating a situation where decisions about election law violations could be made by one political entity without checks and balances. This power grab would allow Warner’s office to issue mandates to local prosecutors and would significantly limit the autonomy of other branches of government in making prosecutorial decisions.

These actions point to a disturbing trend where the Secretary of State is not only encroaching on the rights of individuals but also consolidating control over election-related investigations, raising questions about the ethical limits of government power and the potential for political misuse of state resources.